@1 Why I am Here Writing

So I am here right now, writing. On Substack. In my room. During my sabbatical.

Why? Why on earth would I exchange the time and effort of my youth to write and share these thoughts?

This article is a justification for personal writing, and the next will be on why I would even share this.

Why Write

Writing Informs Thought

The first message I want to impart is that you write to think. It is the process of making your ideas clear and apparent to yourself. This may seem illogical because surely your own ideas are more evident in your own head than outside it. But if you are like me and have tried to explain something you have just learnt to someone else, you will have experienced times where your ability falls short of expectations. The act of verbalising these ideas for the first time demands much more engagement with the material than you would have given before, as you aren’t able to fall back on rehearsal. Translating ideas from the nebulous neural fog in our brain to something concrete and symbolic—language—is an expensive operation, and hence calls on more of the brain’s faculties to participate. As you pause on the vagaries of a particular point, your critical thinking may kick in and ask, “Why is this the case? Why couldn’t you do it this other way instead?”. You might be able to give immediate answers by calling upon reason or connecting the dots with your memory. This added boost of concentration can be channelled towards two ends: 1) identifying and rectifying holes in your understanding, and 2) solidifying and enhancing your existing understanding so that it ‘makes more sense’.

There is another way in which writing can transform thought. Like painting, or filmmaking, or designing, writing is a creative pursuit that channels your will’s drive to make something new. The journey from nothing to something involves an evolution for the artist in addition to the artefact. As the composition is constructed, the artist has time to reflect. As they sit and muse on their subject, serendipity will have them see their work-in-progress from a different perspective. This will inspire them to adjust and change direction. There is a continuous iterative process of thinking → doing → changing the artefact → receiving feedback → having new thoughts. By the end of the project, both the invention and inventor are somewhere different from where they started.

Effective writing leads to action

I have a common pattern of behaviour that I am in the process of graduating from: rumination. I could go over the same idea over and over in my head, making virtually no progress. Instead, I will procrastinate and defer actually investing any time in furthering the thought by writing.

Why is it so uncomfortable and exhausting to write? The answer is nuanced because not all writing is the same! Different systems of writing will lead to wildly different outcomes. I will focus on two: Perfect Prose and Free Form.

Perfect Prose

Perfect prose is the habit of a perfectionist. Writing begins on the very first line, and proceeds by crafting (perfectly) each sentence one after another. Talk about slow. You can’t build any momentum, and in reality the approach is not conducive to generating insights. Instead, you have the hat of an editor on and are ruthlessly killing any sign of imagination before it has the chance to express itself. This blocks thought.

I want to offer a potential explanation as to why perfectionists don’t naturally deviate from their losing strategy of perfect prose. Their greatest flaw is, of course, they have uncompromisingly high standards. Each sentence that they write is being silently evaluated against this standard, even against criteria that may be of secondary importance like “Is the sentence elegant?” or “Do I sound smart?”. Unsurprisingly, unreasonable standards are rarely met, and they fall short of expectations. This sends a negative signal to their self-esteem about their own worth or efficacy. To defend against this discomfort, they reject this smaller and more real image of themselves. So, they persist with this ineffectual practice in the hope that they will soon meet that high standard. The irony is that in forcing the situation, they end up hampering their own capabilities.

Free Form

Instead of constraining yourself to the order of sequential writing, free form asks you to embrace chaos, let loose, and write whatever comes to mind. Total stream of consciousness. Some practise 5-, 10-, or 15-minute timers where they jot down anything and everything that they think of. This is supposed to be fast-paced, energetic, and engaging.

My variation: For me at least, the approach does not need to be completely unstructured. I opt for scribbling thoughts into hierarchical bullet points. I find it easier to spot the scaffolding of my ideas, which serve as markers to inspire the next chain of thought. I keep going in short sprints until my bullet-pointed thesis is dense enough that each bullet point could roughly correspond to a sentence, each group of points a paragraph or section. Then, I might rearrange ideas a little, and then flatten this “thought tree” into actual prose, and pad out the sentences with supportive copy.

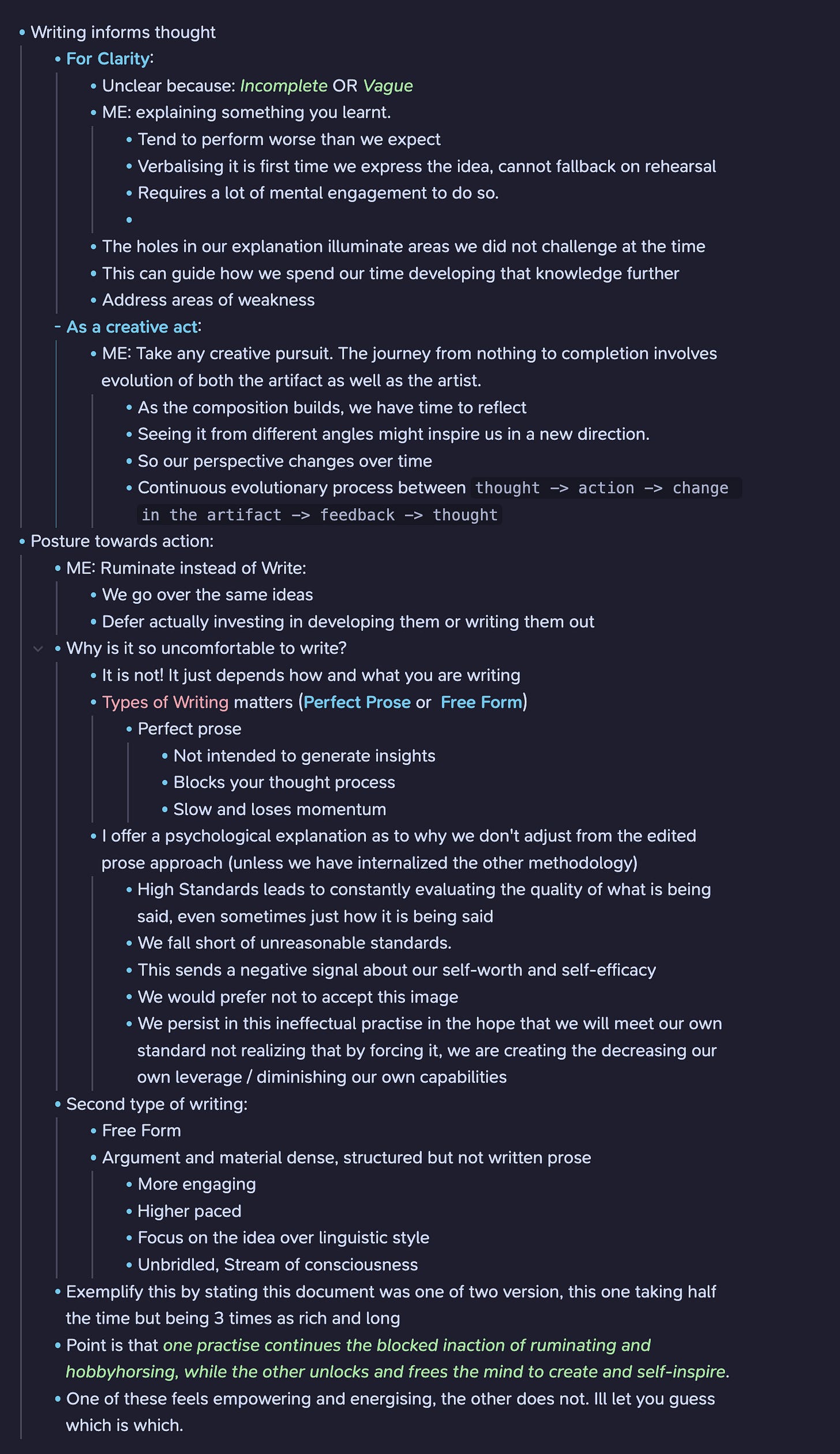

To exemplify the difference in results, I had originally written my first draft in a perfect prose way. Typical of me. Three hours and all I have to show is 500 words. Good thing I caught myself and began embodying the principle I profess. In my second take, I rewrote everything from scratch and doubled my word count in less time. Below is what my free form notes for this article look like. Very similar to what you see here and written in less than 25 minutes.

At its core, the practice of free form focuses on ideas over linguistic style. Remember that writing is for thinking, and if we privilege form over function, it's just a waste of time.

One practice continues the blocked inaction of ruminating, while the other unlocks and frees the mind to create and self-inspire. One of these feels empowering and liberating; the other does not. To return to this section’s purpose, the right type of writing can move you into a state of action and change. Ideas get advanced, you feel like you’re making progress, and the momentum of your action energises you.

Nice read, and so I'm going to take the opportunity to try a bit of writing here - you describe linguistic style as a secondary concern over the ideas themselves (at least when free-form writing), but naturally many use-cases greatly benefit from being stylish. Obviously these cases tend to be when the writing is intended to be read by others (in a personal substack article, perhaps) - but equally, sharing thoughts with other people is a good way to further refine them.

You may enjoy the (short) book "Stylish Academic Writing" by Helen Sword, who gives her perspective on this in the world of academia - where too often the writing falls short in this regard.